Tucker, one of the only scientists in the world studying the phenomenon, says the strength of the cases he encounters varies. Some can be easily discounted, for instance, when it becomes clear that a child’s innocuous statements come within a family that desperately misses a loved one.

But in a number of the cases, like Ryan’s, Tucker says the most logical, scientific explanation for a claim is as simple as it is astounding: Somehow, the child recalls memories from another life.

“I understand the leap it takes to conclude there is something beyond what we can see and touch,” says Tucker, who served as medical director of the University’s Child and Family Psychiatry Clinic for nearly a decade. “But there is this evidence here that needs to be accounted for, and when we look at these cases carefully, some sort of carry-over of memories often makes the most sense.”

In his latest book, Return to Life, due out this month, Tucker details some of the more compelling American cases he’s researched and outlines his argument that discoveries within quantum mechanics, the mind-bending science of how nature’s smallest particles behave, provide clues to reincarnation’s existence.

“Quantum physics indicates that our physical world may grow out of our consciousness,” Tucker says. “That’s a view held not just by me, but by a number of physicists as well.”

Little Controversy

While his work might be expected to garner fierce debate within the scientific community, Tucker’s research, based in part on the cases accumulated all over the world by his predecessor, Ian Stevenson, who died in 2007, has caused little stir.

Michael Levin, director of the Center for Regenerative and Developmental Biology at Tufts University—who wrote in an academic review of Tucker’s first book that it presented a “first-rate piece of research”—said that’s because current scientific research models have no way to prove or debunk Tucker’s findings.

“When you fish with a net with a certain size of holes, you will never catch any fish smaller than those holes,” Levin says. “What you find is limited by how you are searching for it. Our current methods and concepts have no way of dealing with these data.”

Tucker, whose research is funded entirely by an endowment, began his reincarnation research in the late 1990s after he read an article in the Charlottesville Daily Progress about Stevenson’s office winning a grant to study the effects of near-death experiences.

“I was curious about the idea of life after death and whether the scientific method could be used to study it,” Tucker says.

He began volunteering within Stevenson’s department and after a few years found himself a permanent researcher in the office, where his duties included overseeing the electronic coding of Stevenson’s reincarnation cases.

That coding took years—Stevenson’s handwritten case files reached back to 1961—but Tucker said the work is yielding intriguing insights.

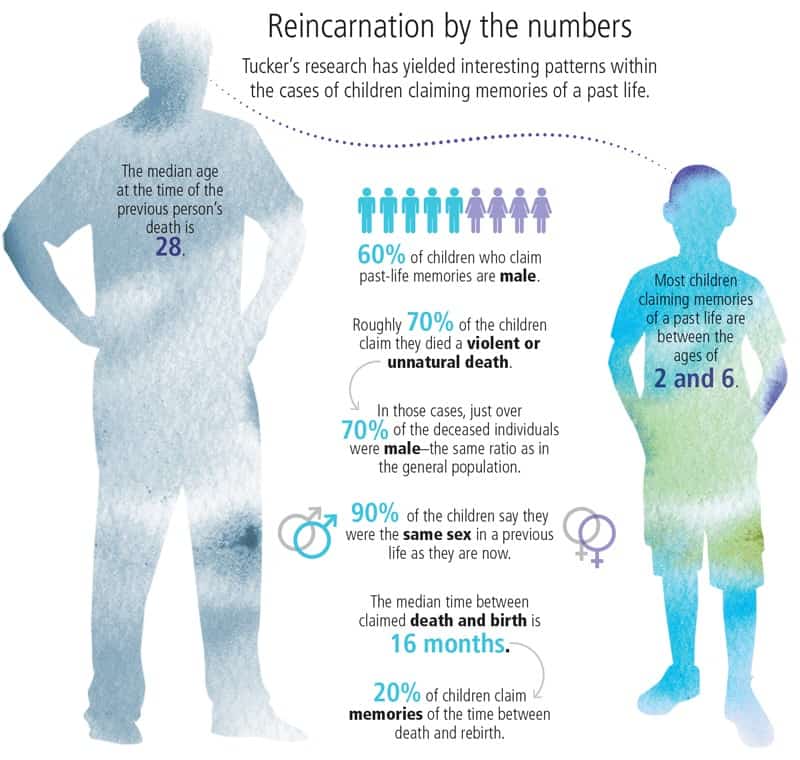

Roughly 70 percent of the children say they died violent or unexpected deaths in their previous life. Males account for close to three-quarters of those deaths—almost precisely the same ratio of males who die of unnatural causes in the general population.

More cases are reported in countries where reincarnation is part of the religious culture, but Tucker says there is no correlation between how strong a case is deemed and that family’s beliefs in reincarnation.

One out of five children who report a past life say they recall the intermission, the time between death and birth, although there is no consistent view of what that’s like. Some allege they were in “God’s house,” while others claim they waited near where they died before “going inside” their mother.

In cases where a child’s story has been traced to another individual, the median time between the death of that person and the child’s birth is about 16 months.

Further research by Tucker and others has shown the children generally have above-average IQs and do not possess any mental or emotional disorders beyond average groups of children. None appears to have been dissociating from painful family situations.

Nearly 20 percent of the children studied have scarlike birthmarks or even unusual deformities that closely match marks or injuries the person whose life the child recalls received at or near his or her death.

Most children’s claims generally subside around age 6, coinciding roughly with what Tucker says is the time children’s brains ready themselves for a new stage of development.

Despite the otherworldly nature of their stories, almost none of the children exhibit any signs of being particularly enlightened, Tucker says.

“My impression of the children is that while a few make philosophical statements about life, most are just typical kids,” he says. “It might be a situation similar to not being any smarter on the first day of first grade than you were on the last day of kindergarten.”